Second Thoughts On the Early Christian Church Discovered at Megiddo

My first post on the discovery of an early Christian church in Megiddo contained a distinct whiff of sarcasm as I reflected on all they hype that usually accompanies the report of a new archaeological discovery in the Holy Land.

My first post on the discovery of an early Christian church in Megiddo contained a distinct whiff of sarcasm as I reflected on all they hype that usually accompanies the report of a new archaeological discovery in the Holy Land.After thinking this over, however, and after reading what little more I could find about this particular site I have found myself becoming more excited about what may have been found.

It does appear that this "church" does not fit the model of any other known fourth century church previously found in the region. Constantinian-era church were almost always built on a site with distinct and specific historical or traditional ties with either Old or New Testament events. Such churches were always built in some variation of a basilica, a Roman architectural layout with an east-west axis and an apse in the front of the worship space (facing east).

It does appear that this "church" does not fit the model of any other known fourth century church previously found in the region. Constantinian-era church were almost always built on a site with distinct and specific historical or traditional ties with either Old or New Testament events. Such churches were always built in some variation of a basilica, a Roman architectural layout with an east-west axis and an apse in the front of the worship space (facing east).In some cases, churches of this period and later were also built on top of the ruins of older Roman or Greek temples, often in ruins from earthquakes and subsequent abandonment.

The Megiddo "church" does not fit any of these expected criteria. It stands in the middle of what must have been part of the Megiddo sprawl, on an otherwise un-noteworthy plot of land and being essentially a simple square in design.

The Megiddo "church" does not fit any of these expected criteria. It stands in the middle of what must have been part of the Megiddo sprawl, on an otherwise un-noteworthy plot of land and being essentially a simple square in design.So far as I have heard, it does not appear to "match up" with any Byzantine chronicles or journals kept by Holy Land pilgrims nor did the preliminary reports indicate the usual sort of accompanying artifacts that would indicate that the "church" had at any time been a pilgrimage site or shrine.

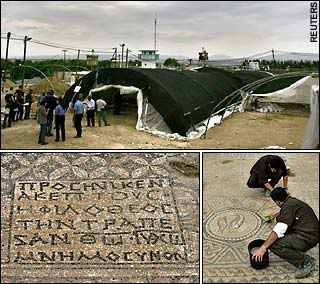

Indeed, the only evidence that it might have been a Christian church at all is the large mosaic (covering 576 square feet or 24'x24') that covered an interior floor (or possibly a courtyard). This remarkable mosaic was without any doubt whatsoever created by a Christian community and intended to establish a uniquely Christian environment for those who, for whatever reason, made use of that area.

This evidence is tantalizing in its uniqueness and in the way it can fit reasonably into a time of history when Christianity was officially "illegal" but frequently tolerated during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD of the Roman Empire.

This evidence is tantalizing in its uniqueness and in the way it can fit reasonably into a time of history when Christianity was officially "illegal" but frequently tolerated during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD of the Roman Empire.From the New Testament we know that, while "church" buildings were built for that specific purpose, local Christian communities did meet together in designated places. Most often these meetings would take place in private homes large enough to accommodate the gathering.

Is it possible that what has been discovered at Megiddo is a 2nd or 3rd century "house church?" Could the local Christian community, along with the owners of the "house" have provided culturally appropriate decoration for the place where they gathered for worship and fellowship each week? Could various members donated the cost of the mosaic and other furnishings and their names have been incorporated into the mosaic inscriptions as a means of honoring their gifts?

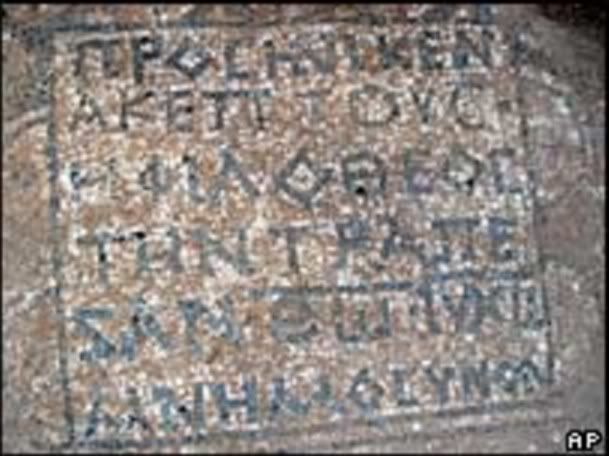

One inscription declares,

"The God-loving Aketous has offered this table to the God Jesus Christ, as a memorial."It is already being speculated that this may refer to what is now called (in Protestant churches) the "Lord's Table" or "Communion Table" where the Sacrament is celebrated as either a "remembrance" or as the "real spiritual presence" of the Lord. This would be in contrast to the Roman Catholic use of an "altar," which denotes a place of sacrifice, where Jesus Christ is actually sacrificed again and again as the "real presence" of his body is broken and the real presence of his blood is poured out during the celebration of the Mass. (Note: This last sentence was honestly challenged in the comments section as misrepresenting the Roman Catholic theology of the Eucharist. I encourage you, the reader, to read both that comment and my reply in the "comments" for this post.)

Is it possible that the early Christians celebrated the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper (as commanded by Jesus when he said, "Do this...") on a table instead of an altar? If so, this would have important and far ranging implications theologically and provide new and exiting insight into the beliefs and practices of the early Christians.

Also curious in this discovery, is that the vast majority of the names recorded in the mosaic are those of women.

It is a fact that, before the universal acceptance and accreditation of Christianity by Emperor Constantine in 386 AD, those most attracted to the Christian faith were the poor (especially widows), slaves and women. This is not surprising since the Good News of the Gospel raised all of these people to the level of equals with everyone else ("For all who have been baptized in Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek or male or female. For we are all one in Christ Jesus.") . Men, on the other hand, had to take a step down in status when they became a Christian. Within the Christian community they were now equal to women, slaves and the poor. The world changing teachings of this gospel was accepted, of course, by many men who sensed the truth in what it contained. According to the culture of the times, it was these men who took the leadership and teaching roles in the faith communities.

Even so, just as it was Jesus' women disciples who provided much of the support and (possibly) much of the funding for his ministry, it appears that it was the women who provided the support and funding for the decoration for whatever it is that has been unearthed in Megiddo.

According to a "Dr. Beeri," who submitted a comment to an article on this subject in Haaretz.com,

Of interest to me is the fact that all the names of Greek (or Latin) names. None has even a remote resemblance to a Hebrew or Jewish name (as was the case with all of Jesus' disciples and apostles).the... article states the women's names (listed in one inscription) were Primilia, Kirikea, Dorothea and Kresta...

This might indicate that, even in these earliest centuries following the fall of Jerusalem by Trajan in 70 AD, the Jewish-based identity of the first Christians in what we now call the "Holy Land" had already been "taken over" by Gentile (or at least Greek-speaking) believers.

Dr. Yotan Tepper, who is heading up the excavations, pointed out another of the inscriptions (from the Washington Post),

"Gaianos, also called Porphyrio, centurion, our brother, having sought honor with his own money, has made this mosaic. Brouti has carried out the work." Tepper said the inscription refers to a Roman officer -- many officers were early converts to Christianity -- who financed the structure's (or at least the mosaic's) construction.Also of interest is the fact that a Byzantine era church was sitting on top of the structure with the mosaic. Dr. Tepper indicated that, although one artifact found contiguous with the mosaic could be dated to late 3rd century AD the actual date for the mosaic would not be determined until datable artifacts could be excavated from beneath the mosaic.

As a Christian pastor with an interest in biblical archaeology and early church history, I am almost overwhelmed by the potential implications of this discover. It could, of course, turn out to have been worthy of my earlier sarcasm. On the other hand it could wind up reshaping everything we know about the Christian churches of the 3rd century AD.....at least in Megiddo!

As a Christian pastor with an interest in biblical archaeology and early church history, I am almost overwhelmed by the potential implications of this discover. It could, of course, turn out to have been worthy of my earlier sarcasm. On the other hand it could wind up reshaping everything we know about the Christian churches of the 3rd century AD.....at least in Megiddo!Other substantive articles on this subject can be found here and here.

A HUGE hat tip to Archeoblog

<< Home