Morality & Hiroshima In the Context of the Evolution of Warfare

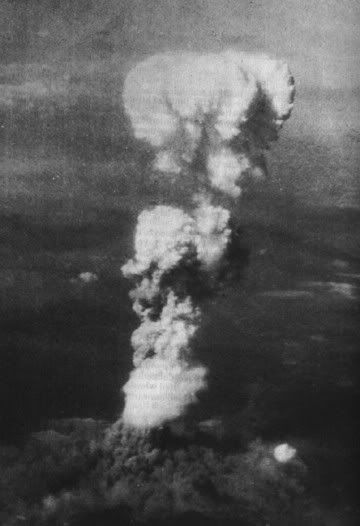

Yesterday was remembered as the 60th anniversary of the dropping of the first atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Next week we will remember the dropping of the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

Yesterday was remembered as the 60th anniversary of the dropping of the first atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Next week we will remember the dropping of the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki.Few events of the past century have generated so much controversy, soul searching, second-guessing and moral introspection as the decision made by US President Harry Truman to drop those two bombs.

Somehow, in remarkable fashion, after many millennia of human warfare, those two bombs struck most of the world simultaneously as having crossed a line that should never again be crossed.

This unusual and nearly unprecedented reaction is worthy of note.

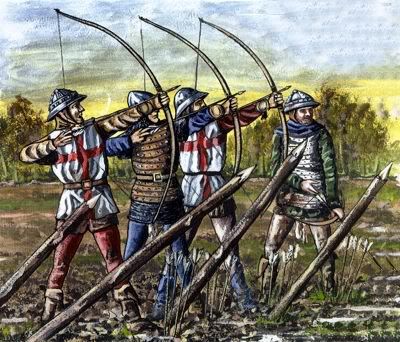

When the first man with a bow and arrow shot down an enemy at 20 yards, did the world cry, "foul?"

When English archers at the battle of Agincourt launched ten thousand arrows at once, obliterating and routing the French army, did the world cry, "foul?"

When besieging armies starved cities into oblivion, did the world cry, "foul?"

When gunpowder and cannon made the thick, stone walls of castle fortresses useless, did the world cry, "foul?"

When two cannon balls were tied together with chain and shot at the legs of charging troops, slicing off dozens of legs in the process, did the world cry, "foul?"

When aeroplanes began strafing and dropping bombs did the world cry, "foul?"

The answer to all these questions is, of course, "No."

In fact, advances in military power and effectiveness throughout history have been met not only with eager imitation by everyone else, but with admiration as well.

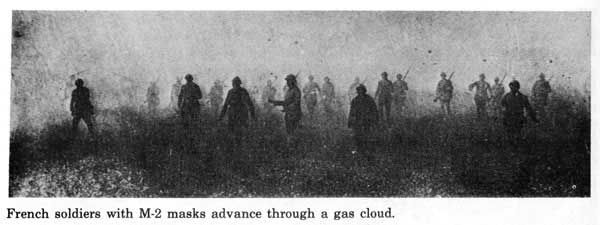

This unbroken evolution of destructive firepower proceeded across history with hardly a hiccough.....until World War I. Even then, it wasn't the trenches that posed a moral difficulty. It wasn't the diseases and infections that produced most of the casualties that posed a moral difficulty. It was the mustard gas.

Somehow, the world was, for perhaps the first time, almost universally repulsed by this new innovation in warfare. It is doubtful that before it was actually used, anyone would have considered it to be any less "moral" or "ethical" than any of the other methods of "mass killing" that were being implemented and used in that grotesque parody of war.

But, having been used, the world took a good hard look at where this particular military technology would lead them. And said, "Never again!"

The moral judgment came after its use. Not before. And that moral judgment has effectively restricted and condemned its use ever since.

A similar situation took occurred with the dropping of the two atomic bombs on Japan.

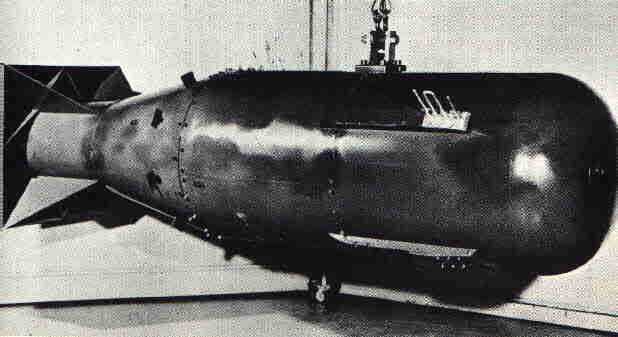

Before they were actually used, Germany and the United States were both working hard to find a way to control the power of the atom. Germany surrendered before unlocking the secret. The United States succeeded.

Whether to use this power to bring a swift and conclusive end to the war with Japan was seriously debated within both the scientific and political communities at the time.

The moral issues, however, did not revolve around the use of the bomb itself, but regarding how the bomb should be used. After the bombings of Dresden and Tokyo, there had been a loud outcry of disgust from many in America....even from within the military itself (subesquently, some pilots reportedly refused to fly bombing missions targeting civilians).

The debate primarily concerned whether it was morally acceptable to target a large civilian population area or not.

In retrospect, it was clearly a mistake, both militarily and ethically to have chosen to drop those bombs in the locations chosen. Prior moral outrage over such tactics should have been sufficient to have led President Truman and his advisors to have chosen differently.

In this, however, the moral issues concerning the atomic bomb were no different that those which concerned the more conventional fire- and blanket-bombings that had preceded them.

The moral judgment on the atomic power itself did not fully emerge until, as with the mustard gas, after it had been used

.

The effects of radiation on human life, and the vast wasteland created instantly by the concussion and heat, stunned the world into near speechlessness.

As with the use of mustard gas in World War I, the world took a good hard look at where this particular military technology would lead them and said, "Never again!"

I believe it is unfair to read that moral judgment back into those years, months and days before the detonation of those bombs. We know today what those who made the decision to drop those bombs did not. We cannot hold them guilty for the use of this technologically marvelous weapon that virtually guaranteed the end of World War II.

As with mustard gas and other chemical and biological warfare technologies, the genie of nuclear bomb technology has been kept in the bottle by international common consensus and the grace of God.

Those who use such technologies after the moral verdict has been made will always be guilty of a far greater sin than those who used them for the first time.

In the New Testament, the Apostle Paul tells us that sin did not appear until after "the Law" was revealed. Before the Law and its sworn acceptance by individuals and nations, there was a certain innocence from ignorance. But, having heard the Law and its judgments, there was no more excuse. Behavior that had once been, at best, "controversial," now became banned, forbidden, tabu, kapu.....sin without excuse......condemned by all.

Such, I believe, is the case with nuclear weapons.

They have been used once......twice.....the judgment has been made and the verdict unsealed......"Never again!"

And, by God's grace, this will remain the Law of the Land until the end of time.

It does us little good to curse the past and render judgments based on what we learned and understood after the fact.

On the other hand, it does us a great deal of good to apply that knowledge and understanding to our present times and be guided by them as we follow history into the future.

<< Home