"The Great Raid"--A Review

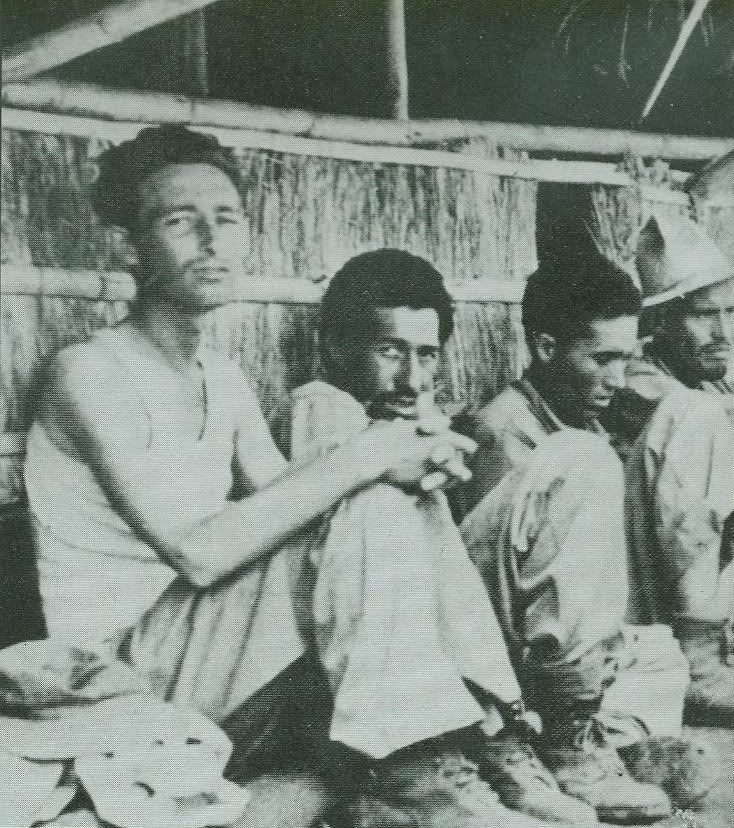

American captives at Cabanatuan POW Camp

This afternoon I had the numbing privilege of seeing the movie, “The Great Raid,” at the Mililani Theater Complex.

Having previously read (some years ago) one of the two books on which the movie was based (“Ghost Soldiers,” by Hampton Sides) I was well familiar with both the details of the raid that rescued 500 Americans from the Japanese prisoner of war camp at Cabanatuan and the historical context in which the raid took place (Note: An estimated 1200 Americans died at Cabanatuan before its liberation on January 30, 1945).

The movie was a faithful, step-by-step adaptation of the book I had read. Just as I had remembered, the movie captured the business-like planning, the meticulous timing of the logistics, the crucial participation and sacrifice of the Filipino “underground” army, the merciless and ceaseless abuse of the American prisoners by their Japanese captors, the selfless and heroic efforts of an expatriate American nurse to maintain a clandestine flow of smuggled medicine for the prisoners and, of course, the bravery and discipline of the American Rangers who led and carried out the raid. As the ending credits explain, the raid remains the largest successful rescue operation in American military history.

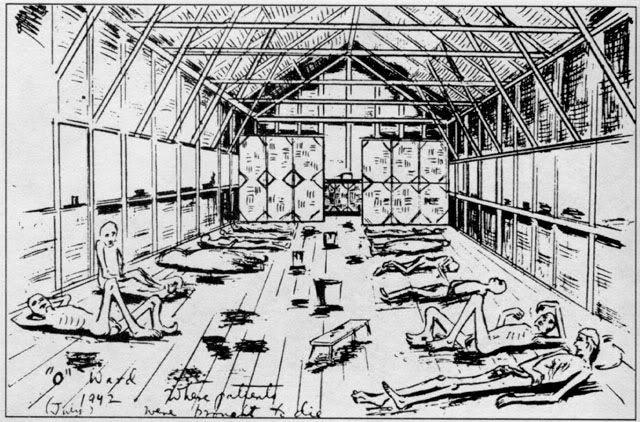

Cabanatuan: Zero Ward, drawn by Medical Officer Eugene Jacobs

The movie opens with segments of film from contemporary WW II archives intermixed with “antiqued” segments shot during the filming of the movie itself. These black and white images eventually segue into full color until, at the end of the movie, the black and white format returns.

This “framing” of the film suggests that what we are about to see is simply a “snapshot” of one incident among many others. As the black and white morphed into color, I found myself transported back in time to 1945 where I was present and contemporary with the events taking place.

While the movie explicitly address several serious themes (in particular the question of what constitutes “glory”) there was little or no preaching. The moral evil of the Japanese policies and attitudes towards prisoners of war were simply depicted as they were with no narrative comment added….nor was any necessary.

The film was graphic and emotionally wrenching. The violence was comparable in its authentic explicitness to that shown in the now infamous opening scenes of D-Day in “Saving Private Ryan.” The depiction of the prison camp and the surrounding geography of the Philippines (although filmed in Queensland, Australia) and even the recreation of Manila under the Japanese occupation were meticulously and convincingly portrayed.

Cabanatuan Cemetary, drawn by Medical Officer Eugene Jacobs

The characters (and those who portrayed them) were shown as normal men and women placed in extraordinary circumstances. The lack of “big name” actors with easily recognized faces allowed the film to take on an almost documentary realism.

There is irony in this since (although the movie makes no mention of it) the Rangers really were accompanied by an army film crew complete with a movie camera. Actual images taken on the raid were smoothly integrated into the movie, especially at the end, and certainly helped to enhance the sense of authenticity that permeates the film.

There is a somewhat contrived love story woven into the fabric of the film. While it served to add a “human touch” to what was otherwise a grueling and exhausting two+ hours of violence and suspense, and while it provided a motivations for the American nurse to risk her life and for one of the forsaken and abandoned prisoners to cling to life and hope, it was too small a matter to counterbalance the overwhelming gravity of the actual drama of the raid. Even so, while the movie might have been historically better without that sub-plot, the final effect would not have been as complex and compelling.

The difficult and fateful decision by President Roosevelt and his military advisors to abandon the 20,000+ American troops (and 50,000 Filipino soldiers) following the siege of Corregidor and their heroic but futile withdrawal to Bataan was rightly understood by those prisoners of war to be a tragic betrayal unprecedented in American history.

In the end, however, the soldiers who risked and sacrificed their lives to ensure the freedom of these same prisoners three years later, demonstrated not only that they had not been forgotten but also provided a fitting sense of atonement and redemption as the film came to an end.

While I would not recommend this movie for anyone younger than high school age, I would also hope that any adolescent that might go to see the movie would have, at the very least, an opportunity to discover where the Philippines and Cabanatuan are located on a map of the world and also have some understanding of the raid’s historical context before they enter the theater.

Like “Schindler’s List” and “Saving Private Ryan,” I believe that “The Great Raid” is of sufficient quality and stature to continue to refresh and sharpen our memories of a time that is fast fading into a slough of revisionism. “The Great Raid” represents a time, a place and a group of people who represent far more than just themselves. The good and the evil depicted in the various characters remind us of the choices being made by people and nations today….and their consequences.

The movie offers those who have the eyes to see, both a word of warning and a word of hope. It also affirms that personal and national philosophies and beliefs have moral consequences and that some beliefs lead to consequences that are, morally speaking, vastly superior to others.

<< Home